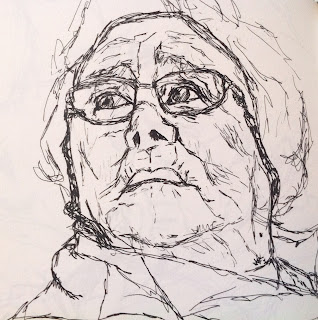

As a doctor, I am interested in the important, but often

overlooked, interface between art and medicine, as this provides a unique

insight into the human condition. I wanted to celebrate

people’s narratives and histories, and experiment with different methods of

recording and documenting these narratives. It is also interesting to see

how some narratives become distorted by a disease process. I wanted to highlight

how these narratives impact upon the next generation.

I did not want my work to

be morbid, but instead something beautiful, celebrating life.

In our society, death and dying are seen as the last taboo. As a culture, our attitudes towards the elderly and the dying are not as positive as those held by other cultures. This is reflected in the recent political reports indicating that care in the fields of old age and palliative medicine needs to be done better. I have often witnessed people being defined solely by their disease, dehumanising them.

I decided to use fabric in this piece because of the narrative connotations associated with it... ‘spinning a yarn’/ ‘picking up a thread’/‘to fabricate’, etc. Also fabric has a certain delicacy and vulnerability that I wanted to take advantage of for this piece.

Fabric also has very personal and intimate associations with people throughout a lifetime, for example, fabric is the first thing we come into contact with when we are born, surrounds us throughout life in the form of clothing and bedding, and is the last thing to touch our skin in death.

I was really pleased with the transparency of the net curtains used to work on. I felt this represented the vulnerability of these people and how this group of people can be forgotten by society, hidden in their homes and looking out through their net curtains.